For the Noble knight, resplendent in his bright livery, mounted on his superb destrier, supremely powerful, invulnerable to injury in his suit of plate armour and lord of all he could survey, the advent of the powerful winched crossbow and, following in quick succession, the hand gun, each with it’s armour piercing capability, must have seemed like a nightmare come true. That a lowly foot soldier could bring down a fine warrior with the pull of a finger and no martial skill must have seemed a blasphemy of the highest order.

These weapons were still quite experimental in the 15th century and there never were very many of them, no massed ranks, no devastating volleys, no “fire when you see the whites of their eyes!” for this reason they are ideal in the skirmisher role.

They were, for the most part, wielded by foreign mercenaries, who were well paid for their arcane knowledge and expertise. Europe produced a limitless supply of mercenary troops throughout the era. European nations, including England, had been warring with each other pretty much constantly for centuries so there was always a surplus of soldiery looking for work and the spoils of war.

Many of these, armed with the new powerful windlass crossbow and the constantly improving hand gun, were available for hire during the wars of the Roses. Edward IV used many Burgundian troops in the 1470’s and Margaret of Anjou and Henry Tudor employed French, German and Swiss.

Never Mind the Billhooks has opened up a whole new world for me, gaming the wars of the Roses is a process of constant learning, of new discoveries about history and the development of weapons and tactics. In Billhooks skirmishers are deployed as small bands of men armed with bows, crossbows or hand guns.

As far as I can see, there is no evidence to support the existence of 15th century troops skirmishing in the manner that we have come to think of as skirmishing, the formal “skirmish line” of latter days. There can be no doubt that it happened in the form of individual bands of warriors harassing the enemy, defending river crossings, holding vital junctions, scouting enemy positions and as such the bands of skirmishers in Never Mind the Billhooks are a good representation of this.

Having played a few games now, I am persuaded that hand-gunners and crossbowmen are definitely the key troops for this role as they cost the same as archers but have an ability to pierce the armour of the dreaded men at arms!

One problem with both these weapons was the time they took to load and prepare for shooting. While performing these actions the user was pretty much defenceless and made a good target. One solution to this problem was the use of a pavise.

For three points per unit pavises can be purchased to increase the defensive ability of these vulnerable missile men. But what is a pavise? Where does it come from? How is it made? What did they look like? How were they decorated?

Here’s what I found out. The pavise is thought to have taken its name from the North Italian city of Pavia where it perhaps originated, in the 13th century. The pavise quickly evolved into two main forms: the larger standing pavise that could be propped up in front of the archer or crossbowman, and the relatively smaller hand-pavise favoured by other classes of foot-soldier, according to an anonymous chronicle of about 1330.

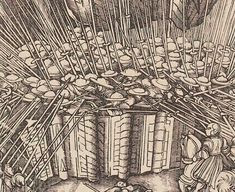

Both types of pavise are clearly depicted in the fine woodcuts prepared by Hans Burgkmair between 1512 and 1518 for the Triumph of Maximilian I and, in other works, by Albrecht Durer

It was perhaps through the influence of Italian mercenaries that the use of the pavise spread to other parts of Europe, most notably Bohemia where it was employed to impressive effect by the Hussite revolutionary armies of the late 14th and early 15th centuries. It was also used by German, Swiss, Burgundian and French troops.

Of oblong form, usually with a medial gutter running down its rear, its use by archers and other classes of infantry extended from the late 14th century to the early 16th century. Although some of it’s kind were no more than hand-held shields, others, were of a sufficient size to allow them to be propped up in front of the crossbowman to provide him with temporary shelter while he spanned and loaded his weapon.

Made of wood covered with gessoed canvas and fitted at its upper end with an iron ring bearing a leather suspension-loop, and at its lower end with an iron handle; and the lower edge fitted with one or two projecting iron spikes attached by rivets.

In accordance with the tastes of the later Middle Ages, pavises tended to be decorated with a colourful design that typically involved the arms of the town or city for which they were made.This one bears the coat of arms of a famous medieval Florentine family - the Bounamici. The Latin inscription bordering the pavise translates as "Praise this most holy abbot, venerate this most holy abbot

The original pavises were massive and had to be supported by a specialist pavise-bearer whose job it was to crouch down with it in front of the archer or crossbowman that he was assigned to protect. He must have been a worthy individual as he was paid more than the marksman!

There is a collection of pavises kept at the Town Hall of Erfurt in Saxony and in the Erfurt Anger-Museum.

The Erfurt pavises are fitted at their lower ends with a pair of projecting iron spikes that could be driven into the ground so as to better resist the onslaught of the enemy. A particular tactic of the Bohemians was to form a solid wall of pavises.

Not all the Erfurt pavises are of Bohemian origin.

Pavise decoration varies widely. Mythical beasts and particularly dragons feature a lot…

…as do images of saints…

…and scenes demonstrating the retribution of God. The letters IHS are commonly found on grave-stones and in churches from this period denoting the latinised form of the first three letters of the name Jesus from the Greek alphabet.

“Of oblong, shape with rounded corners, tapering slightly to its lower end which projects downwards in the form of an iron-reinforced central spike; and made of wood covered with gessoed canvas; the front painted on a white ground with a red saltire separating four golden fire-steels ornamented with fleurons (flower shaped ornamentation) each accompanied by a black briquet of elongated quatrefoil form and surrounded by red flames” Overall height: 48 in; Overall width: 22 1/4 in

http://myarmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.php?t=2711&postdays=0&postorder=asc&start=0

“The saltire can be interpreted as the cross of St Andrew, a Burgundian emblem that, along with the fire-steels, briquets and flames seen on the pavise under discussion, became part of the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece, founded by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1470, with St Andrew as its patron.”

My experience of skirmishers in Billhooks is that they are excellent at neutralising artillery, they can provide a nuisance value if they can get behind a formation, and are capable of taking down MaA as easily as billmen.

I decided to create two units, one each of arbalesters and harquebusiers, and although I wanted the opportunity to paint some pavises, I also wanted the option to use them without pavise. So I made removable pavises.

I took the plastic pavises from the Perrys European Mercenaries set and drilled out a slot for a length of brass rod which I superglued in place

I was careful to drill behind the ”iron” spike leaving it intact

I cut out some pieces of 1mm - plasticard 23mm x 20mm to make the bases. I cut up some Renedra 20mm square bases to create 3 mm wide strips that I Plastic glued on the front of plasticard along its short edge

I drilled a small hole in the plastic strip to accommodate the brass rod and superglued them in place

and then I painted them!

Burgundian crossbowmen in their traditional argent and azure saltire gules livery. The shields as described above bearing the red diagonal cross, the saltire, of St Andrew. All figures are Perry Miniatures from their European Mercenaries box.

Here is the captain. He wears a similar livery jacket to his men but has a yellow border to indicate his rank.

On his sallet he flies a small flag bearing his company number. I guess it would also have served as a wind direction indicator!

I missed a trick here as he should be holding a standard and they had some right beauties! A project for another day maybe

Another Burgundian. A cranequin hangs from his belt. This was a device that used a winding handle to operate a wormed thread that pulled the bow string into place. It was lighter and easier to use then a windlass

Edward IV enjoyed close ties with the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, and used Burgundian mercenaries.

Another lovely Perry figure, his open sallet is of a more European design. At his waist hangs the traditional quiver made of wild boar hide and a cranequin.

The gent in the middle is using a windlass it’s likely that this was needed for a more powerful crossbow than the cranequin could wind

For the hand-gunners I decided on a mixed band of mercenaries from all over Europe, representing, perhaps, a predecessor of the free companies of a later era.

This man is wearing the white and violet of Louis de Bruges, of Burgundy. His pavise is possibly of French origin so it may well be the spoils of war. His face is pock marked and scarred from repeated use of the Harquebus, no doubt particles of soot and burnt powder grains would have tattooed his face giving him a permanent badge of honour

This man is wearing red and yellow livery of a Swiss mercenary. His pavise is based on one from the Erfurt collection although it’s origin is unknown as, untypically, it bears no city’s coat of arms

This man wears a livery, white and green, of the Holy Roman Empire and his pavise bears the arms of a city in Bohemia.

This man wears expensive clothing. His sword pommel, hilt and belt buckle are of gold. Hand gunners and artillerymen were the best paid mercenaries of this era. His gun looks remarkably modern in its shape and like a modern rifle it is pulled into the shoulder.

Reconstructions of these weapons show them to be more accurate than once believed and were probably quite effective at short range.

My take on the Bounamici pavise.

The pavise! Was it effective? Probably, why else would you lug it around?

It certainly provided an advertising space, maybe these shielded marksmen got themselves sponsors?

A new addition to my army, great fun to paint and a welcome distraction from all those serried ranks of bows and bills!

Reading

The Medieval Soldier in the Wars of the Roses -Andrew W Boardman

Medieval Military Costume-Gerry Embleton

Opsrey Men at Arms 144- Armies of Medieval Burgundy 1364–1477 - Nicholas Michael

A really interesting piece about pavise's and some great painting too.

ReplyDeleteThank you Bod, I am glad you enjoyed it.

ReplyDeleteNice Mike, great brush work on the pavises. Quite a few in French museums locally.

ReplyDeleteI placed my supportpoke by drilling directly through the top handle then the pole leaning on the at a 45%. Have a look at my Breton ordonnance company on my blog.

Cheers

Matt

Thanks Matt, your Bretons look very nice . You are a lucky man to have such a resource so close to your home!

Delete